Wanting to tell the story of the Tarot means attempting to trace back through time in search of a past that is as obscure as its origins are mysterious. This has given rise to countless fanciful theories, multiplying across numerous books and websites. From the Book of Thoth to a creation by Marsilio Ficino, from a secret code devised by Abbot Suger to the testament of Mary Magdalene, or even the work of Atlanteans or extraterrestrials, the wildest ideas flirt with the inconsistencies that historical gaps allow to sneak in.

So, rather than discussing what we believe, let us talk about what we actually know.

The Tarot has many beginnings because, before being called as such, it seems it first bore the name Naïbbi.

In the decree of Charles V in 1369 prohibiting games, playing cards are NOT mentioned. We can therefore deduce that at that time, the Tarot (or simply playing cards) did not yet exist, and thus cannot predate this decree. Of course, this does not mean that the “knowledge” or artistic, historical, and cultural (not to say cultic) roots did not exist before then. But the game itself did not exist—at least not as a deck of playing cards. And this nuance is crucial because, as I explain in my workshops, it seems the original function of the images that would later become the Major Arcana of the Marseille Tarot was… as works of art!

On August 30, 1381, in the records of a notary in Marseille, a card game is mentioned under the name nahipi. This is the first historical mention of a card game, and thus its formal entry into the realm of play. If the images used to illustrate these cards existed before 1369, it is only between 1369 and 1381 that their use became playful.

Elsewhere in Europe, mentions appear in legal documents from around the 1370s. For instance, a decree from Florence dated May 23, 1376 bans a recently introduced game called naibbe. This helps establish the limits of its possible origin.

This is further confirmed by Dominican friar Johannes in a treatise from 1377, in which he speaks of a Ludus Cartarum (game of cards). He describes it as composed of four kings and/or queens, followed by two marshals (perhaps valets and knights?) and a series of ten pip cards grouped by emblem families.

Later, a chronicle from the city of Viterbo in Italy tells us: “In the year 1379, a Saracen named Hayl brought to Viterbo a card game from the land of the Saracens, which they call Naib.” The term “Saracen” at the time in Europe referred to someone with dark skin. Could this explain the name of the only trump card without a number, representing a traveler, called the “Mat“? Mat, as in dark-skinned, carrying a bundle in which perhaps lies the card game he brought to the West?

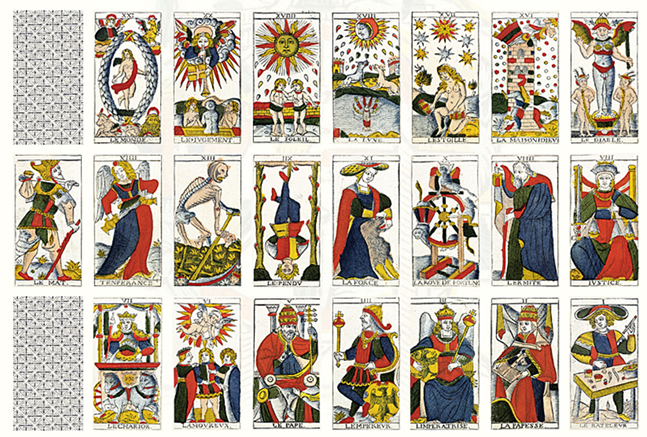

To find a deck of cards structured like our modern Tarot, we must wait until September 16, 1440, when a Medici notary mentions it. A year later, in 1441, the famous (and oldest known) Tarot deck called “Visconti di Modrone” (also known as Cary-Yale) was born.

In that deck, we can recognize, among others, the Hanged Man, the Wheel of Fortune, the Chariot, Strength, the Pope, the Emperor, the Empress, the Sun, the Moon, the Star, the Magician, Death, the Tower, the Devil, Temperance, and the Seven of Wands…

From that point on, the decks grew in popularity and spread across Italy in increasingly sophisticated forms. While the earliest decks were richly illuminated, large, thick, and expensive (with an illustration on the front, a blank back, and both sides glued to a rigid plate known as the “soul” — probably the origin of the term “lame” in French to describe Tarot cards), creators gradually began to simplify their designs. It wasn’t until the 16th century that the cards were labeled with names and numbers, especially upon arriving in France, which is why the Tarot and its name are so strongly tied to French tradition.

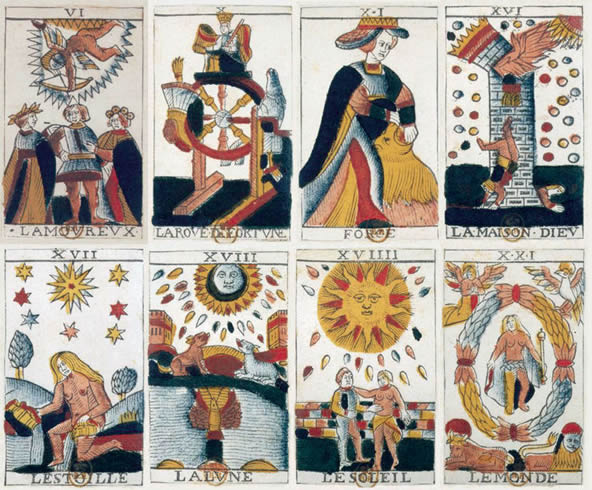

In France, Tarot became especially popular with decks known as “Viéville,” “Noblet,” and “Payen/Dodal”:

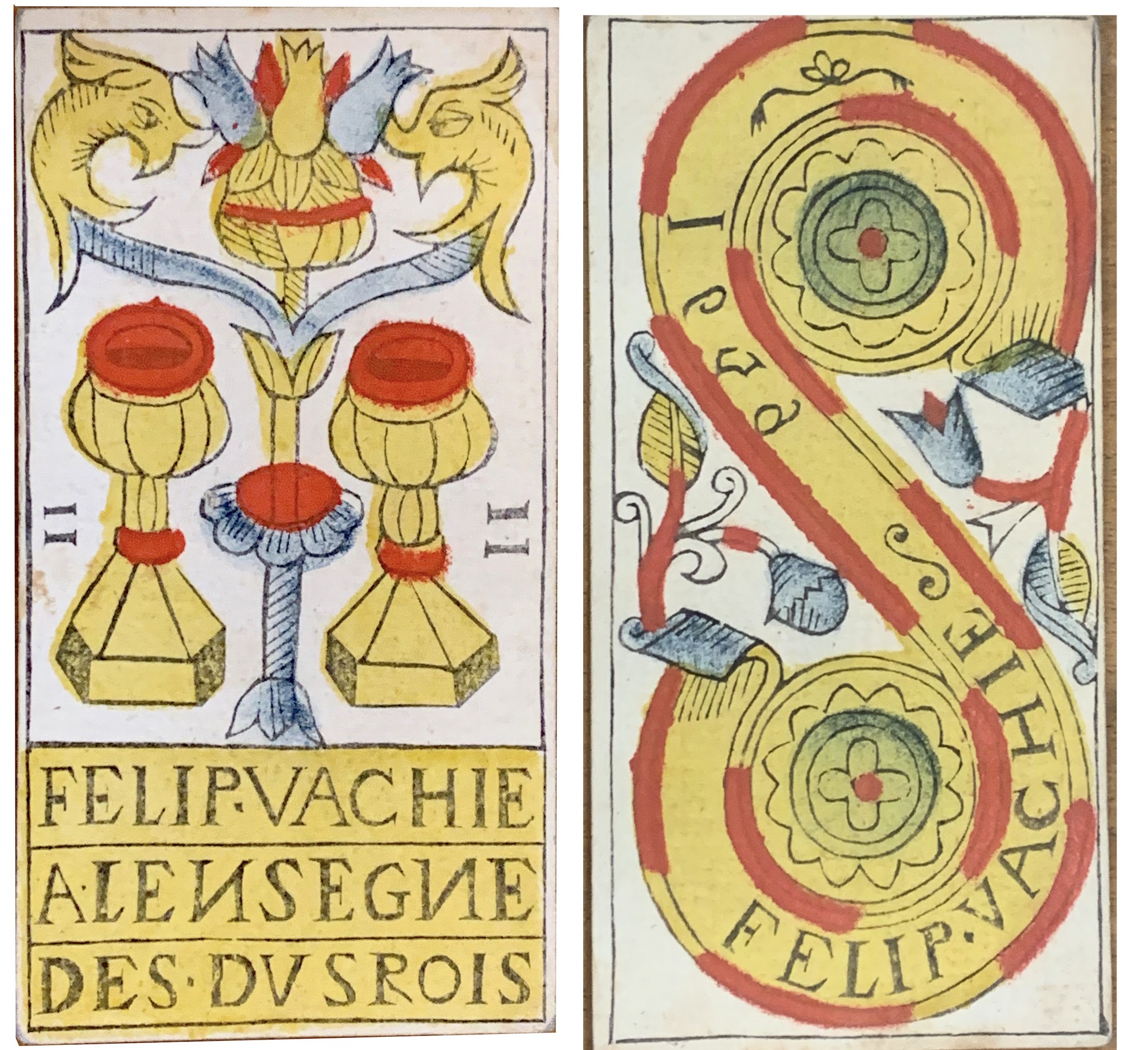

EDIT: Since 2023, following an auction, a “new” deck has surfaced — in reality, it is the oldest known Type 1 Tarot deck to date: the deck of Philippe Vachier, dated 1636:

These decks, produced in Lyon, are classified as “Type 1” before making way for “Type 2,” the one we know today, which appeared with the Madenié Tarot (Dijon, 1709). So, the so-called “Marseille Tarot” is Marseille in name only.

As we can see, the Tarot deck was likely not created by Egyptian gods, Atlanteans, or aliens, but rather is a purely human creation. And while its origins are obscure, it nonetheless has a more or less traceable history.

Why then so much mystery? For several reasons. First, we do not know its original author. Then, we don’t know the cause of its creation. Finally, we don’t know its original purpose. Enough to fuel the imagination of even the most creative minds!

Writings offer few answers to these questions. But based on the evidence we have, we can suppose that the creation was first artistic (perhaps the whim of a genius painter?), followed by a divinatory use, and finally, a role in gambling and games of chance. My dear Jean-Claude Flornoy (may he rest in peace) believed that this card game held the wisdom of Companions and builders, with pedagogical virtues. A sort of instruction manual for life, especially for those who could not read. While this is not proven, I find the poetry of this hypothesis quite beautiful.

For further reading on the history of gambling and the Tarot in general, I recommend two excellent books:

“Jeux, réjouissances et distractions au Moyen-âge” by René Cintré. Not very focused on Tarot, but highly informative on the emergence of games in our regions.

“Histoire du Tarot” by my dear friend Isabelle Nadolny—a must-read for anyone seeking a serious, scholarly account of the Tarot’s history (Isabelle is a historian, which spares her from the usual fantasies we often see in Tarot literature).